The short-lived Centre de Formation de Fonctionnaires et Magistrats Algeriens (CFFMA)

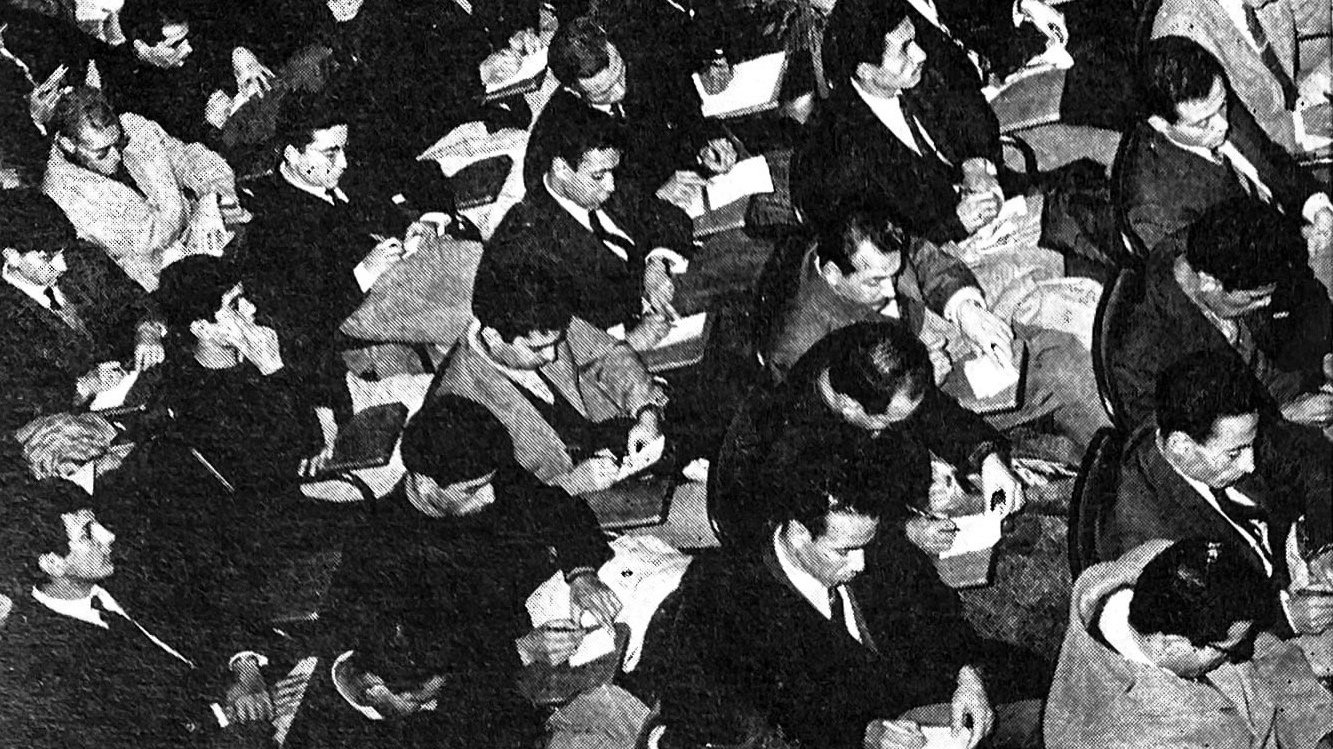

CFFMA students at work (Source: Archives Nationales de France)

Mere months after the Algerian War of Independence drew to a close in 1962, a first cohort of Algerian diplomats in training were beginning their studies at the Centre de Formation des Fonctionnaires et des Magistrats Algeriennes (CFFMA) in Paris.

Few Algerian ‘indigènes’ had been trained to hold high office within the civil service under colonial rule, and the retreating pied-noirs had weakened and indeed actively sabotaged institutions of learning (for example, the University of Algiers and its library were deliberately burned down on 7th June 1962). The training of administrative, legal and diplomatic personnel was agreed as part of the Evian Accords, the peace deal between the Algerian Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN) and the French government. However, according to files held at the Archives Nationales de France, the resulting CFFMA would face several material, political and diplomatic difficulties during its early months. For the diplomatic trainees, the geopolitical issues bound up with their training were put into stark relief as they sought to find their place in relation to the international community, to their former colonial enemy, and to the fast-growing city of Paris.

The question immediately to be considered was where this training would be held? Up until its independence, Algeria’s highest civil servants had been trained in France’s Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA) – as Algeria had been an integral part of France. Africans from other former French colonies, on the other hand, had been trained separately by the Paris Institut des Hautes Etudes d’Outre Mer (IHEOM) since 1958. A note circulated in 1962 spelled out that training the Algerians at the ENA, which they would prefer, would ‘undermine the mission’ of both the ENA to train French administrators, and the IHEOM to provide training to international students sent primarily by former colonies, by opening the doors of the ENA to foreign students and devaluing the diploma of the IHEOM by comparison.

The solution, then, was to create the CFFMA, which would come under IHEOM director François Luchaire and follow a very similar but slightly different set of courses to the IHEOM, involving many of the same trainers. Though still in Paris, the CFFMA and its students would be physically separate from the IHEOM located on the site of the former Ecole Coloniale on Avenue de l’Observatoire. On the governing body, there would be representatives of the Algerian government as well as the French ENA.

The CFFMA immediately faced two significant problems in the autumn of 1962, as they were about to start their training programmes. Firstly, they needed to find accommodation, both for classes and for the students. There was no room at the IHEOM, so the CFFMA had to ask around Paris, renting teaching rooms at various other institutions of learning, including the Institut des Hautes Etudes de l'Amerique Latine, the Centre de Droit Comparé, and the Musée Social. As there was not yet an Algerian Embassy established in France to help the students with finding accommodation, they approached various associations specialised in providing “accommodation for Muslims” and ended up renting several rooms in the new suburb of Villemomble, about an hour east of Paris. The accommodation problem was compounded by a second issue – that the CFFMA team did not know until the courses began precisely how many students they would have, and what they would be studying.

In the end, the CFFMA ran three courses: one diplomatic, one consular, and another in general public administration. Although it is clear from the early CFFMA documentation that more subsequent cohorts were expected in Paris in the years to come, the first CFFMA cohort would be its last.

Students immediately complained about their living and studying conditions, as they faced long and costly journeys between their accommodation in Villemomble and their various classes around central Paris. Unable to work in a single library or student space they ended up in local cafés, spending money they didn’t have and being distracted from their studies. It was clearly far from straightforward for the French authorities to accommodate the Algerian students they were committed to training. On two separate occasions, one of the consular trainees, Rafik Bensaci, was arrested on historic charges relating to pro-FLN activity during the Algerian War, whilst another student was arrested for desertion. Though they were released after an intervention by Luchaire, these episodes underline the material, political and diplomatic difficulties faced by the CFFMA during its early months.

In perhaps a reflection of these difficulties and the geopolitical imperative driving Algeria towards greater independence from France, training was swiftly moved to schools in Algeria itself, with the CFFMA providing visiting lecturers and other pedagogical support as well as continuing to organise placements in France. By 1966 the practically defunct CFFMA was subsumed with the IHEOM to launch the reorganised Institut International d’Administration Publique. Though brief, the CFFMA’s story exemplifies how power relations operate at various geographical scales, with the training itself requiring and entailing a series of diplomatic practices that mediate these power relations.