Tutelage of African diplomats: a (geo)political and pedagogical problem

Immanuel Kant famously wrote that “Enlightenment is man’s release from his self-incurred tutelage”, pointing to the political and pedagogical imperative for individuals and societies to reach a point of maturity defined by independent judgement and action. We see tutelage as referring to both pedagogical and (geo)political processes where guardianship and instruction are held in tension. It remains an underexplored aspect of much-discussed socialisation in IR, and one that is important for understanding the colonial/postcolonial context.

We need therefore to be attentive to possible ways in which the African diplomats in training actively resisted and overcame constraints placed upon them by the institutions and societies in which they lived, worked and received training, whether in the pursuit of ‘emancipatory enlightenment’ or otherwise. We are also attentive to the ways trainers pursued or frustrated this same goal, adapting their methods and course content, and problematising the generalisability of their pedagogy, knowledge and practice.

Transforming the ‘Ecole Coloniale’

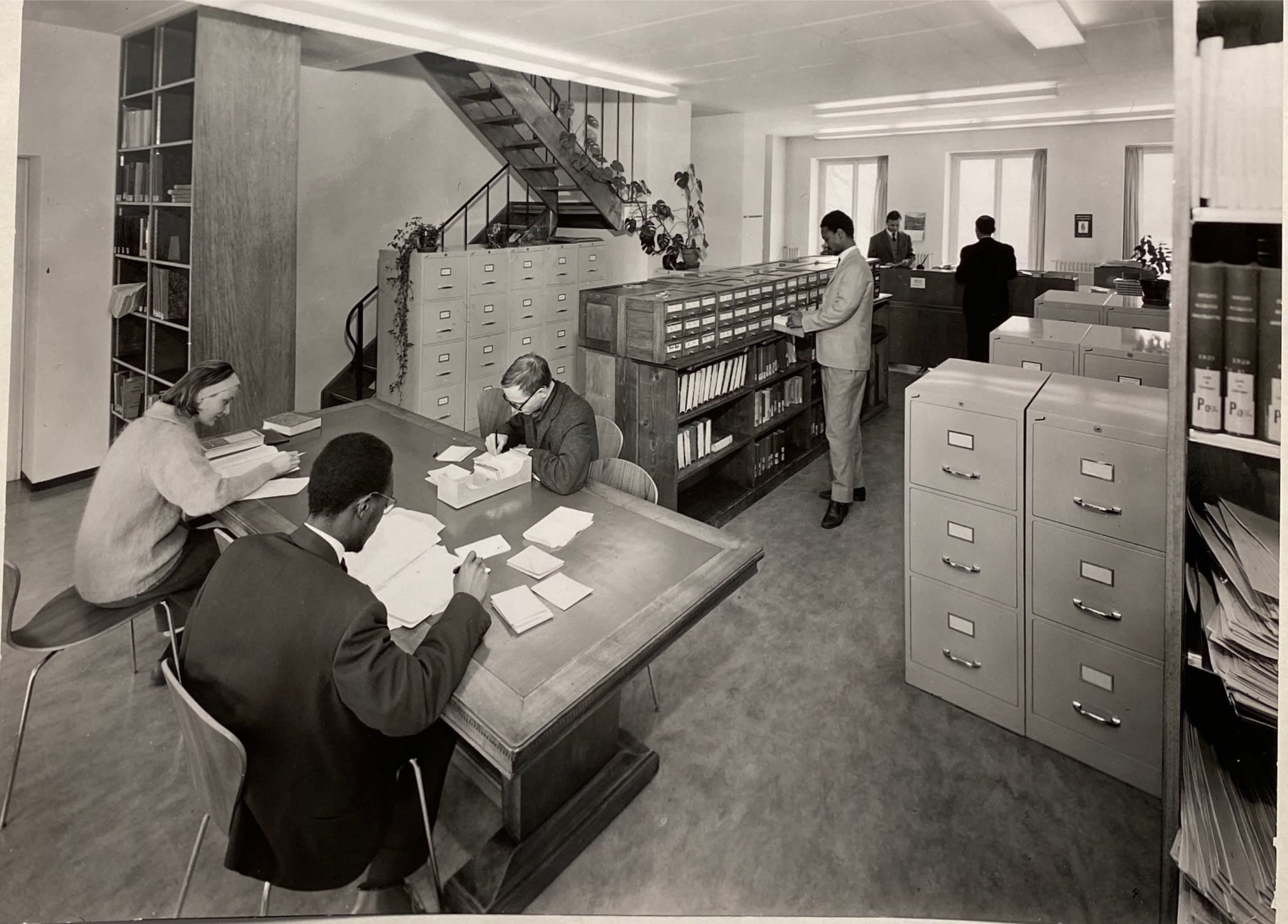

In Paris the former ‘Ecole Coloniale’ became the place for French-funded diplomatic and general administrative training first for former African colonies, then for the wider world under the rebranded ‘Institut International d’Administration Publique’ or IIAP from 1968. The buildings nonetheless retained their colonial character, styled after various Moorish, sub-Saharan and far Eastern motifs. Although we have few photographs of what the building was like at the time, building plans from 1968 included the urgent need "to modify, at least for the most used areas, the character of the architecture, already contestable in itself, which risks offending trainees coming from certain parts of the world".

While it isn’t clear from these plans what exactly might have caused offence, it is clear that the architecture that had only a few years before projected a sense of French mastery over the peoples and cultures of its empire, could now be offensive or embarrassing. Their removal resulted in a sort of white-washing, though clearly some of the arches and doorways that formed the fabric of the building were retained. For the trainees arriving to the school for their courses, the reminders of the recent colonial past would have been all around.

When the famous student protests of May 1968 engulfed Paris, the following graffiti appeared:

- Graffiti noticed in the toilets close to the cafeteria on 6/6/1968 -

No to the inappropriate and colonial teaching methods of the IIAP

No to alienation

No to the cheap training of the IIAP

No to the favouritism of the management

Students of the IIAP are accomplices of French imperialism in black Africa. Let that sink in - it endangers the whole continent.

Down with France’s neo-colonialism in Africa

Down with its military intervention (Gabon) and economic intervention (Ivory Coast)

Down with the puppet African heads of state

No to segregation

No to the La Boëtie ghetto

(Source: Archives Nationales de France)

We don’t know who exactly was responsible for these graffiti, but they suggest that some African students at the IIAP were critical not only of French neo-colonialism and interventionism, but specifically identified the IIAP’s role in perpetuating what they called French imperialism, partly through ‘colonial teaching methods’. What’s more, that records of these graffiti were kept indicates that the school management were taking these criticisms seriously – after all, the French government’s key rationale for funding the institute was to “earn inestimable friendship capital” by fostering ties with and between its students.

What these colonial teaching methods might have been we are left to surmise by examining the remainders of course guides, lecture notes and the like found in records from the time. Beyond the physical location of the school in the former ‘Ecole Coloniale’, the curriculum was prescriptive and inflexible and most classes took a didactic pedagogical approach. The diplomatic training course was the only one to bring trainees from across different cultural backgrounds together – the other courses at IIAP were kept separate by continent in order to ‘avoid psychological problems’. Trainees were trained rigidly according to French principles, and undertook several formal assessments to attain a passing grade. Junior trainees here, it would appear, had little power or influence over the conditions of their training in the early years of independence.

Contested assessment on the Carnegie Programme

In comparison with the IIAP, the Carnegie programme in Geneva was light on assessment and not very prescriptive in its methods, allowing fellows the freedom to engage in their choice of seminar and lecture programmes. There were even seminars given on such potentially controversial topics as neo-colonialism, socialism and the non-aligned movement.

The approach wasn’t without its critics. In 1967 the lecturer Gilbert Etienne wrote of his frustration that in failing to tackle the problem of trainees that were too “lazy or incompetent”, the course might “indirectly contribute to the many evils that are ruining Black Africa", by sending insufficiently prepared diplomats to “take on tasks that their Western colleagues will only take on after long years of practical experience”. He suggested introducing January exams to get all trainees working seriously from the start and to prevent the “lazy or incompetent” ones from completing the course.

However, Etienne would have been aware that only the previous year these January exams had been tried and failed. A letter signed by the whole cohort of trainees in December 1965 formally declared “We the undersigned, trainees of the Carnegie Endowment gathered for a General Assembly […] considering our reasons as explained to [the various directors of the course] have decided not the take the tests prepared for us”.

We the undersigned, trainees of the Carnegie Endowment gathered for a General Assembly […] considering our reasons as explained to [the various directors of the course] have decided not the take the tests prepared for us

Geneva, 6th December 1965

(Source: IHEID Archive)

These reasons were later summarised by course director Jacques Freymond as boiling down to the “fear of low marks having consequences on one's future career”. Instead, he wrote, his course would try a system of individual tutoring from 1966, hoping that “the human contact thus established between the professors and the trainees will lead to an improvement in the quality of their work”.

Read through the lens of postcolonial tutelage, this example indicates that the diplomatic trainees of newly independent states were not mere passive participants in their course, but ready to contest and resist the use of arbitrary power by their trainers. For their part, the trainers appear to grapple with the problem of fostering genuine independent thought and action on the part of their trainees, not wishing to play any role in maintaining African states in a position of ‘tutelage’ through ignorance. In this example, the political issue of national independence had become a pedagogical problem for the diplomatic training course.